Vietnam POWs to be honored 50 years after Nixon celebrated them with historic banquet

by Heather Robinson

From The New York Post

Nixon was deep in the Watergate scandal but hosted the 591 POWs held in Vietnam at the White House in a banquet held in a huge tent on the South Lawn. Dozens will reunite Wednesday for a reenactment 50 years on. Richard Nixon Presidential Library and Museum/NARA

It was — and still is — the biggest banquet in White House history.

In a tent on the South Lawn on May 24 in 1973, 1,600 people gathered to honor 591 prisoners of war who had finally been released from Vietnam.

On Wednesday dozens of the survivors of the 591 will be honored again at a reenactment of the meal at the Richard Nixon Presidential Library in Yorba Linda, California.

Fifty years ago, a long nightmare had finally ended for the POWs who were held for up to eight years, tortured, beaten, starved, and used as propaganda pawns by the Communist regime.

The dinner was hosted by President Nixon, a brief relief from the unfolding national nightmare of Watergate, and was itself a rare moment of unity during the slow end of a war which had divided the nation.

In the tent on the South Lawn, the former POWs, in full dress uniform, were entertained by Bob Hope and Sammy Davis Jr., and mingled with senior military and government officials to celebrate their return. Richard Nixon Presidential Library and Museum

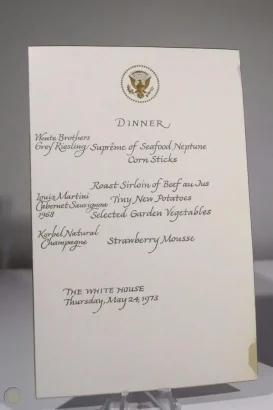

The reenactment Wednesday will be so exacting that the menu and table centerpieces will be the same as in 1973.

Not present of course will be the celebrities the Nixon White House brought to the reception: comedian Bob Hope emceed and the POWs and their families mingled with John Wayne, Jimmy Stewart, Phyllis Diller, and Sammy Davis Jr.

Many at the dinner then, and now, were survivors of the Hanoi Hilton, the prison infamous for its torture.

On stage Irving Berlin (second left) sang his composition God Bless America, with Nixon and his wife Pat joined by Sammy Davis Jr. (center) and Bob Hope (right), the MC of the evening. Richard Nixon Presidential Library and Museum

This was the menu for the dinner. An identical menu will be served at the 50th reunion dinner, at tables set with identical centerpieces. Nixon Presidential Library and Museum

Its most famous inmate was John McCain, then the Navy pilot son of the supreme commander in the Pacific, Admiral John McCain Jr., and later the Republican senator from Arizona and presidential candidate.

A smaller number of the POWs had been held in jungle camps with horrendous death rates.

But on February 12, 1973, Nixon signed the Paris peace deal to end the war, and the next month Operation Homecoming began.

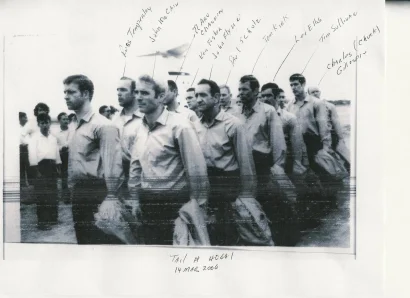

The prisoners — among them Ken Wallingford, an Army infantryman who was captured in 1972 (center) — had endured horrific conditions, forced marches, and torture. Courtesy of Ken Wallingford

Many of the POWs were held at the infamous Hanoi Hilton, a former French colonial repurposed as a torture center for American prisoners, many of them high-ranking. They were paraded as propaganda tools. Getty Images

By April 1, nearly 600 POWs had been returned, and US combat troops had finally left Vietnam.

The war was effectively over, although it was not until 1975 that the evacuation of Saigon marked its humiliating end.

The Nixon Library is not planning any more similar reunions after this week’s, reflecting the inevitable thinning of the ranks of the veterans.

The 591 POWs had been repatriated through Operation Homecoming, which began after the Paris Peace Accords. U.S. Air Force

But the dinner in Yorba Linda will be a chance to honor the survivors while it is still possible — and reflect on their stories of heroism.

The Post spoke to five former POWs, the oldest 91, the youngest 75, about their experiences.

“THEY DIED IN MY ARMS.” FLIGHT SURGEON’S HELL IN PRISON CAMP

Army Flight Surgeon Hal Kushner was on the way to deliver urgent medical care on November 30, 1967, when his Huey helicopter smashed into a mountain.

Knocked unconscious, Kushner woke to see the pilot crushed against the instrument panel, and after clambering from the wreckage with his collarbone and left wrist broken, he saw the rest of the crew strewn across the ground.

Hal Kushner was one of the crew of a Huey helicopter, the workhorse of Vietnam, when it crashed into a mountainside, leading to his capture by the Viet Cong as he trekked to safety. Courtesy of Dr. Hal Kushner

Kushner was held for 1,973 days, and was awarded the Silver Star for his heroism in the prison camps. Courtesy of Dr. Hal Kushner

Then an M-16 machine gun on the helicopter exploded, bullets hitting him in the back and shoulder.

The crew chief went for help, leaving Kushner with the co-pilot, who took 3 days to die.

Alone, Kushner walked several miles and encountered a peasant in a rice paddy.

The man gave him milk — and turned him over to the Viet Cong.

“The leader shot me through my left shoulder,” said Kushner, who showed the man his medic’s card. The man said: “No POW. Criminal.”

They tied him to a door, and beat him with a bamboo rod. His ordeal had just begun.

When Kushner was freed, he was greeted when he landed by his parents. His father wrapped his arms around him.

Now 81, Kushner remembers the horror of his captivity. Other prisoners died in his arms. Brian Carlson for New York Post

First he was held in jungle prison camps.

He and the other prisoners were beaten, starved, shackled, and made to perform slave labor.

One man was so severely beaten he died of his wounds after two weeks of suffering.

There were 27 other Americans, 10 of whom died, and 5 West German nurses, of whom just 2 survived.

“Most of them died in my arms,” Kushner said.

From late December 1972 until March 1973, he was in the Hanoi Hilton.

There, Kushner saw a Life magazine containing a picture of his father playing with his son, Michael — whose existence he had been unaware of. “My wife had been pregnant when I left and we didn’t know it.”

After he returned, he met Michael for the first time one week before the boy’s fifth birthday. “One time, he said, ‘Dad, I’m not used to you yet.’”

Kushner keeps all his decorations framed at home, including the Purple Heart he was awarded for the wounds he suffered when his helicopter crashed, and the Silver Star awarded for saving another prisoner’s life in 1969.Brian Carlson for New York Post

Kushner now lives in Daytona Beach, Florida, with his wife Gail. Brian Carlson for New York Post

Today Kushner, 81, a retired ophthalmologist living in Daytona Beach, Fla., enjoys a close relationship with Michael.

His daughter, Toni Jean was 3 and a half when he left and remembered him when he returned, so “resuming a normal relationship was easier.”

Kushner feels strongly that the way U.S. history is taught lacks rigor. “Vietnam rates a paragraph in most history books,” he said. “Don’t get me started.”

But he does his part: he will be the keynote speaker at Gettysburg National Cemetery on Memorial Day.

“IF WE CAME HOME BITTER WE WOULD STILL BE CAPTIVES,” SAYS PILOT

On November 7, 1967, Lt. Leon “Lee” Ellis was on a mission to bomb the Ho Chi Minh trail, the network of pathways used by the North Vietnamese Army and the Viet Cong, when his F-4C Phantom was brought down.

Surrounded by local militia he was stripped of his flight suit, vest, gun, knife, and boots, blindfolded and paraded from village to village.

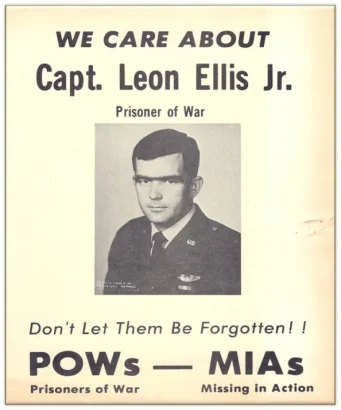

Ellis, an F-4C Phantom pilot was shot down on a bombing mission targeting the Ho Chi Minh trail. He was a lieutenant when shot down, and was promoted to captain.

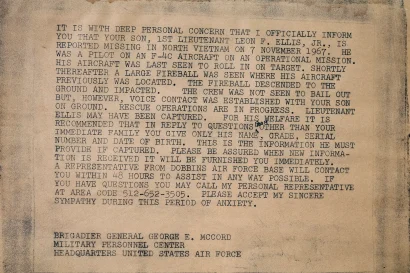

Capt. Ellis’ family learned he had possibly been taken captive by telegram, and warned not to give out more information about him than his name, grade, serial number and date of birth. Robin Rayne/ZUMA for NY Post

Sensing he was approaching a ditch and certain they were planning to kill him, he raised his blindfold and turned.

“I was going to make sure I looked in their eyes.”

But he was only kicked in the rear, to the amusement of his captors.

His initial treatment was fortunate because “a good man” led the local militia.

At home, the war divided the country, but families and friends campaigned to remember the plight of the POWs.

But treatment at the Hanoi Hilton was far worse.

Ellis was made to kneel on concrete for 18 hours and punched and kicked until he agreed to fill out a three-page biography. “I felt so worthless when I got back to my cell.”

Ellis admired the men who found creative ways to express defiance. “One guy said, ‘President Horses–t Minh says’ over camp radio.

“Most of the time they didn’t catch the subterfuge because they didn’t know anything about our culture.”

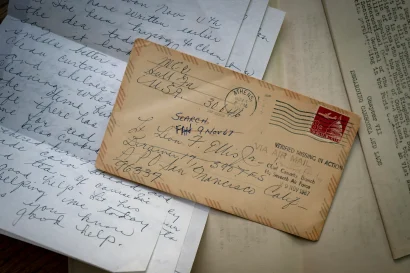

A letter sent to Capt. Ellis (them a lieutenant) was held for him, and he keeps it to this day. Robin Rayne for NY Post

Ellis (fourth row, right) keeps a memento of his freedom, a picture of him and fellow prisoners being released, including John McCain (front row, right).

In October 1969, conditions in the Hanoi Hilton improved, partly after the North Vietnamese Communist leader Ho Chi Minh’s death, and partly because outrage about the POWs was growing back home. Their captors put the men in large cells together.

“Having roommates who know everything good or bad about you, you can’t pretend. We talked about our guilt, our shame, our anger,” he said.

Capt. Ellis’ was given a parade through his hometown when he returned. Ron Sherman/Photographer

Ellis, now 79, of Dawsonville, Georgia, credits Nixon with making the POWs’ safe return an absolute condition of ending the war.

“I think most POWs believe that it was President Nixon’s determination to get us out that brought us home,” he said.

Ellis believes the support the POWs gave each other helped them to rebound better after they came home.

Ellis, 79, left the Air Force as a captain, and says that he came home without bitterness, knowing that he would have been captive to it as much as he was a captive of the Communists. Robin Rayne for NY Post

Ellis became a consultant and wrote a book “Leading with Honor: Leadership Lessons from the Hanoi Hilton” about his time as a prisoner. He lives with his wife Mary in Dawsonville, Georgia. Robin Rayne for NY Post

“We knew that if we came home bitter, we would still be in handcuffs and leg irons,” said Ellis.

“We released that, and now [many of us] are close to Vietnamese people in the US and in Vietnam. We don’t like Communism, but we care about their people.”

“I WAS CHAINED LIKE A ZOO ANIMAL AND PUT IN A TIGER CAGE”

Ken Wallingford will never forget the tiger cages.

“It was like something from medieval times,” recalled Wallingford, 75, of Austin, Texas.

Arranged in a circle inside a bamboo fence with a guard in the center, the cages were to become grim homes for Wallingford and six other American soldiers from April 1972 to February 1973.

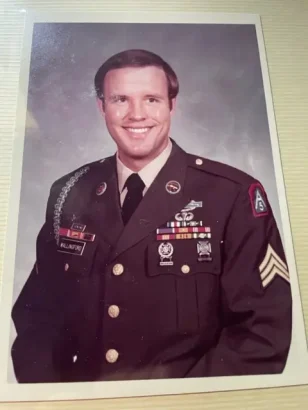

Sgt. Wallingford was captured in 1972. Courtesy of Ken Wallingford

Sgt. Wallingford was freed on February 12 by the North Vietnamese. He had lost 40lb when he was handed over to the US, after enduring torture and near-starvation, chained in a tiger cage but kept alive as a bargaining chip. Courtesy of Ken Wallingford

Wallingford, an Army infantryman, served two tours, first as a sniper, then as an advisor to the South Vietnamese Army during the Tet Offensive.

A sergeant, he was leading a 5-man team when they and the South Vietnamese unit with them were overrun by the North Vietnamese on April 5, 1972.

Seeing “bodies like ants all over the place,” Wallingford prayed, “God, get me out of here alive.”

After two of Wallingford’s team members were killed, he and two others were captured.

Held at gunpoint, injured in 17 places, Wallingford was held up by his friend Ed Carlson as they were marched to the camp in Cambodia.

“They put me in this cage by myself. I had to bend down to get into it. I couldn’t stand because it was five feet high,” he said.

After his return, the former POW wanted to put the ordeal behind him but felt it was his duty to keep the memory of the war alive. He keeps the plate, bowl and chopsticks for his meager food, the sandals and shirt he wore, and the bracelets prisoners were given to identify them. Matthew Mahon for NY Post

“They put a chain around my ankle and locked it to the cage. It made me feel like an animal that is chained in a zoo. But I was thankful to be alive.”

If he wanted to go out, he had to ask permission from “a teenager with an AK-47.”

Bathing was once every two weeks.

The food he was served was a pitiful excuse for a meal: rice and tiny pieces of pork fat, dinner: “one sixteenth of an inch of meat, with hair on it, and a vegetable.”

But when cobras and vipers crawled near his cage and soldiers killed them, he realized he was being kept alive “as a bargaining chip.”

Wallingford, now retired as a real estate broker and Veterans Affairs benefits counselor keeps the Bronze Star he was awarded along with his other decorations. Matthew Mahon for NY Post

Wallingford now lives in Austin, Texas, where he continues to speak about Vietnam to honor those who died — among them the men of his unit killed when he was captured. Matthew Mahon for NY Post

Repatriated February 12 1973, he, Carlson, and the others were flown to a military hospital where they were “fed so well we got sick” — he had gone from 188 to 148 pounds — then to San Antonio, Texas, where he was reunited with his parents on Valentine’s Day.

Coming home, Wallingford wanted to put the war behind him, but felt a duty to share his story.

“I felt it was my obligation to share my story because school books don’t cover much of Vietnam,” he said.

“I was one of the younger POWs, glad to be free. The heroes are those who died on foreign soil serving our country.”

“A NURSE GAVE ME ICE AND A BEER. I PRAYED HE WOULDN’T BE KILLED.”

Bombing a bridge in North Vietnam, US Air Force Captain James Quincy Collins Jr.’s F-105 Thunderchief was shot down in September 1965 by the Viet Cong.

Villagers “threw [him] into the back of a Jeep.”

He remembers the agony, soiling himself on the bumpy ride, then a Hanoi hospital where he glimpsed surgical instruments covered in flies before passing out.

Coming to, he couldn’t move his arms, which had begun to rot and stink. “It’s lucky I didn’t lose them,” he said.

Capt. Collins was a distinguished pilot already when he volunteered for Vietnam, piloting a supersonic F-105 Thunderchief fighter-bomber.

Capt. Collins was captured in September 1965, and held until 1973, spending almost eight years in captivity.

Incapacitated, he begged a Vietnamese nurse for ice.

The man, who fed and bathed him, said “No!”

But the next day, the man entered his room, locked the door, “looked around like he’s casing the joint,” opened his shirt, and withdrew a cup of ice, which he fed Collins.

“Then I asked for beer. He says, ‘Beer? No!’”

But soon the man brought Collins a cold bottle of beer and held it to his mouth to drink.

Collins never saw the nurse again, and never forgot his mercy.

Collins was finally freed as part of Operation Homecoming.

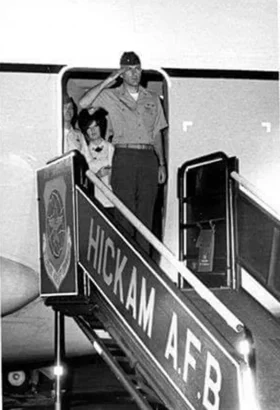

When Operation Homecoming arrived, Collins was one of the men freed. But there was a surprise when he landed: his wife had left him. SSGT Phillip M. Porter USAF / National Archives.

“He probably could’ve been killed for that. I said a lot of prayers that nothing bad happened to him.”

Collins spent the next seven and a half years as a POW, including in the Hanoi Hilton, where he “was in solitary confinement more times than I had hands and feet.”

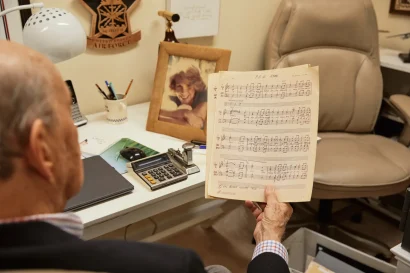

But Collins formed a choir in the prison camp in 1967, and performed at the welcome home dinner held at the White House by President Nixon, where he got to perform “The POW Hymn.”

Collins formed a choir in the Hanoi Hilton and wrote the POW Hymn, then in 1973, was able to sing it at the White House banquet. Richard Nixon Presidential Library and Museum

Collins keeps many mementoes of Vietnam, including the music of the POW Hymn, which he proudly sang at the White House 50 years ago. Ian Mahathey for New York Post

Not everything about coming home was joyful.

“I didn’t have any specific information that my wife wouldn’t be waiting for me, but she wasn’t,” he said.

Instead of being greeted by her, he received a letter stating that “the boys are excited about seeing you again … but we are not going to be living together anymore.”

Collins was imprisoned as a captain but retired from the service as a colonel, with a Silver Star in recognition of his heroism. He retains his dress uniform. Ian Mahathey for New York Post

After retiring from the military, Col. Collins became a real estate broker and wrote a memoir, “Out of the Blue.” Now retired, he lives with his wife Katherine in Charlotte, North Carolin. Ian Mahathey for New York Post

Collins spent the first several years after his return “speaking at patriotic events.”

Now 91, he is remarried to Katherine, and when they go to the dinner from Charlotte, North Carolina, his thoughts will not focus on himself.

“We are going to be thinking a lot about those guys who aren’t there.”

“THEY’D TAKE YOU TO THE POINT YOU WANTED TO DIE.”

Marine Pilot Orson Swindle flew 204 missions before his F-8E Crusader was shot down on November 11, 1966.

Locals threw him into a pit and “did everything they could to humiliate me.”

The second day, “They pinned my forearms between my shoulder blades, bound me with ropes, hoisted me up and beat the living hell out of me.”

Then he was marched to Hanoi.

Orson Swindle flew more than 200 missions until he was shot down in his F-8E Crusader, starting more than six years of captivity which saw him tortured. Courtesy of Orson Swindle

Being shot down was only the start of Swindle’s ordeal. He was beaten from the moment he was captured. Courtesy of Orson Swindle

Those first hours of treatment were repeated over and over again for the next six-and-a-half years.

“The Communists wouldn’t kill you — they saw us as valuable trading chips — but they’d take you to the point you wanted to die,” he said.

But he and the others found a way to communicate, tapping out messages in code through walls to each other.

“When we were beaten and tortured, thrown back in our cell, we would say in code: ‘Good night. God bless you. We’ll talk tomorrow.’ It was like someone holding your hand.

“Some could do better than others resisting pain, but all we asked of each other is do the best you can.”

Swindle became a friend of John McCain, the most high-profile of the prisoners. McCain’s father, Admiral John McCain Jr., was the Pacific theater supreme commander. Getty Images

One of his tactics was to give “names,” the commodity demanded by the torturers: he handed over his high school football teammates, knowing they were safe at home.

John McCain was a cell mate and friend.

“John was strong, a good resister, and funny,” said Swindle.

Of their captors, Swindle says, “We totally hated them. We would just stare at them. That unnerved them.”

Swindle is photographed saluting as he touched down on American soil at Hickam Air Force Base in Hawaii, on his way home. Courtesy of Orson Swindle

Swindle remained in the Marine Corps, retiring in 1979 as Lt. Col. and leaving with 20 honors, including two Silver Stars and the Legion of Merit. Courtesy of Orson Swindle

Swindle said the unpopularity of the Vietnam War at home did not chill their welcome.

His hometown of Camilla, Georgia held a parade for him where Swindle saw members of his high school football team.

“By the way, don’t you guys ever go to Vietnam, because they may be looking for you!” he told them.

Return was sweet. “It was horrifying to be a POW, years of deprivation, pain, suffering, and loneliness,” said Swindle. “You’re in a cell alone, thinking about your family, alone. Then, to be welcomed, what joy.”

Swindle, now 86, lives with his wife Angie in Denver, Colorado. The last reunion will bring a sense of loss. “There were about 600 of us, and now many are gone,” he said. Courtesy of Orson Swindle

But some men encountered surprises. “We came home to happiness for the most part but great uncertainty and some real tragedy,” he said. “Some men had broken marriages, some had lost family … the suffering didn’t necessarily stop with us getting home.”

He remembers the 1973 dinner fondly.

He felt “honored shaking President Nixon’s hand” and happy to see the men he had been with at the Hanoi Hilton, but disappointed not to be seated with them. Attending this year’s reunion gala will be bittersweet, in part because many friends are gone.

“There were about 600 of us, and now many are gone,” said Swindle, now 86, of Denver, Colorado. “I’m glad it’s the last big reunion; it is difficult.”

This entry was written by Heather Robinson and posted on May 25, 2023 at 6:38 pm and filed under Features. permalink. Follow any comments here with the RSS feed for this post. Keywords: . Post a comment or leave a trackback: Trackback URL. */?>