Holocaust survivor wants to testify against Pittsburgh synagogue shooter

by Heather Robinson

From The New York Post

Holocaust survivor Judah Samet was eye to eye with Robert Bowers (inset), the man who allegedly killed 11 of Samet’s congregants at Tree of Life synagogue in Pittsburgh. Now, Samet, 85, wants to testify against Bowers while he can. NY Post photo composite

Judah Samet has been in history’s crosshairs a few times in his long life.

More than seven decades after he survived the Bergen-Belsen concentration camp as a young boy, Samet also lived through the October 2018 mass shooting at Tree of Life, the Pittsburgh synagogue he considered his “home.”

Now, the retired jeweler — who has addressed students, civic organizations and law enforcement about his experiences in the Holocaust — wishes to once again bear witness: Samet wants to take the stand and identify the alleged perpetrator of the deadliest anti-Semitic attack in US history, with whom he says he locked eyes.

But at 84, Samet fears that if the process of bringing alleged killer Robert Bowers to justice continues to be delayed, he could miss his chance to testify.

“I want to testify because he has to pay for what he did,” said Samet on a recent afternoon in his Pittsburgh apartment. “If I don’t testify, and nobody else testifies, he may walk. Justice delayed is justice denied. The man did a crime and he should pay. Three years and four months is plenty of delay. Maybe they should give him Bergen-Belsen rations: one slice of hard bread a day and one cup of soup, which was barely soup.”

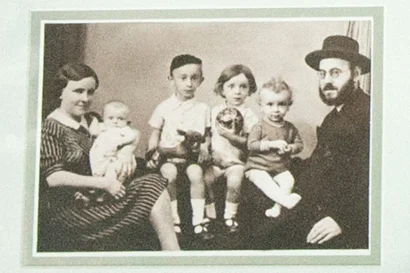

Samet, holding a photo of his parents and siblings, survived the Bergen-Belsen concentration camp during the Holocaust. Chandler Crowell

Bowers is charged with 63 federal crimes and 36 separate crimes in Pennsylvania, including murder and hate crimes. His motives were reportedly white supremacy and anti-Semitism.

Eleven congregants were killed that day, all of whom were known to Samet, including Cecil and David Rosenthal, developmentally disabled brothers who were beloved in the community.

“Cecil and David were mentally challenged,” said Samet. “Cecil was open, not shy, he was the welcoming member of the synagogue. I took them home many times after services. Everybody liked them.”

Two civilians and five police officers were also wounded before Bowers, armed with an assault-style rifle and three handguns, was shot and subdued by police. He surrendered and has been in jail since.

No trial date has been set.

Bowers is charged with 63 counts, including hate crimes resulting in death, in the 2018 shooting. Matt Rourke

Samet does not personally favor the death penalty, “If he is dead he suffers no more,” he said of Bowers. “Put him in a little room with a little window at the top, with no one to talk to.” But he is concerned that the trial’s delay — reportedly due to several factors, including the defense team’s opposition to US prosecutors’ efforts to seek the death penalty — won’t serve justice.

“He’s in jail. He’s no danger to anybody else anymore,” said Samet. “But it’s still dangerous to the psyche of the Jewish community for him not to be tried. Three years … it’s getting to be ridiculous.”

Samet’s resonant voice rises as he describes what happened that fateful October day.

It was a “regular Saturday,” which meant he was going to synagogue. Typically, he arrived on time (“I’d rather be an hour early than one minute late”), but had stopped to speak with his housekeeper.

Samet (second from right) and his family survived the horrors of the Holocaust, although his father died of typhus three days after liberation. Chandler Crowell

Samet, who has difficulty walking long distances, pulled into his usual handicapped spot in the synagogue’s parking lot. “It was eerie, quiet,” he recalled. A man came over to his car’s passenger side window, made a motion for him to roll it down, and said, “’You better go home, there’s a shooting inside the synagogue.’” (The man, Hank Feinberg, a member of New Light synagogue, also survived that day).

Samet then saw a man — a detective, it turned out — with a pistol, alternately ducking behind a wall, then firing toward the building entrance, where another man stood with an assault rifle and “returned three salvos.”

The second man, Samet said, looked directly at him.

“I’m not sure why he didn’t shoot me,” he recalled. “Maybe he figured he needed to shoot at the detective, not at me, because the detective could kill him and I couldn’t. Maybe he couldn’t see me [clearly] through the glare of my windshield. But I saw him. And I remember.”

In the Bergen-Belsen concentration camp, Samet’s mother encouraged him to eat lice so he wouldn’t starve. Bettmann

Samet watched as the shooting “went on between the two of them for a minute, maybe two minutes.”

Before driving away, Samet carefully noted the appearance of the man with the assault rifle.

“The soldier in me came out,” he recalled. “In the [Israel Defense Forces,] they teach you to see who is shooting. I took a mental note to be able to describe him.”

After speaking with the FBI four times, the bureau credited him for his accuracy and consistency, down to specific details of the shooter’s physical appearance and clothing.

Judah’s older brother Yaakov Samet, who was killed in action in Israel’s Sinai conflict in 1956. Chandler Crowell

In January, Bowers and his legal team filed a motion in federal court seeking a change of venue, arguing that news coverage has “shifted the burden of proof to the defendant.”

Nonsense, said Samet.

“He could get a fair trial here. Of course, he will never believe it’s a fair trial because he believes that ‘All Jews must die,’” Samet added, quoting the words Bowers allegedly shouted as police subdued him.

Facing anti-Semitism is painfully familiar to Samet.

“For my family, it’s never over,” he said. “It reminded me of the concentration camps. It reminded me of the fact that one of my brothers was killed defending Israel.” (Samet’s older brother Yaakov Samet, a 20-year-old IDF gunner, died in combat during Israel’s 1956 Sinai conflict.)

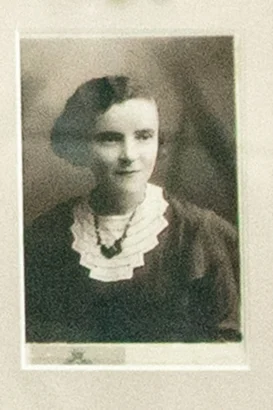

Samet credits his mother, Rachel Marmorstein Samet, with saving his life in the camp. Chandler Crowell

Born in Debrecen, Hungary, Samet and his family spent several months in a slave labor camp in Austria before being sent to Bergen-Belsen for 10 months.

He credits his “fearless” mother, Rachel, with helping him and his three siblings, as well as herself, survive there. His father, Yekutiel, survived the camps but died of typhus three days after liberation.

Of Bergen-Belsen, Samet said, “One thing a survivor can’t relay to anyone is being always hungry.”

He remembers his mother teaching him and his siblings it was ok to eat lice to survive. “She said, ‘They live off your blood, so if you eat them you just take back what they took from you, and blood is protein so it will help you survive.’”

Bowers’ motives were reportedly white supremacy and anti-Semitism. AP

Along with a friend, he would sneak out of the barracks and get as close as he dared to the Nazi officers’ mess hall. He recalled a time when “The Germans came out chewing on something — a [chicken] wing or a pork chop. They finished and threw it on the ground.”

Samet recalled diving for the scrap. “One said, ‘Look at the little Jew pig dog,’” he said. “But I thought, ‘As long as there is something on the ground, who cares what they say?’”

He “never complained” about discomfort, but once developed such a “terrible headache” that he told his mother. She found a big abscess on the back of his head, and brought him to a Jewish doctor in the camp.

The doctor told Samet’s mom, “‘I can’t believe he’s still alive.” He said she would have to hold her son perfectly still, “because ‘If he moves, the scalpel will go into his brain and kill him.’” Miraculously, the surgery was a success. As his mother carried him to the bunk to rest, six-year-old Samet thought, “‘If I’m starving, what does a headache matter?’”

“I’m not sure why he didn’t shoot me,” Samet recalled of the Pittsburgh massacre. Chandler Crowell

After the war, with help from the Hebrew Immigrant Aid Society, Samet’s family went to France, then immigrated to Israel, where he grew up to serve in the Israel Defense Forces (IDF) as a paratrooper and radio man in the 1950s.

During a stint working in a furniture store and living with family in New York City in 1963, Samet met his future wife, Barbara, at a bar mitzvah. Three months later, the couple married and moved to Barbara’s hometown of Pittsburgh, where Samet joined her family’s synagogue, Tree of Life.

They raised their only child, a daughter, Elizabeth, in the synagogue, with Samet, who was working at Schiffman’s, the family jewelry business he would eventually co-own, also employed part-time as a tutor helping prepare boys for their bar mitzvahs.

Barbara passed away in 2013. Elizabeth has two sons whom Samet is looking forward to visiting this spring in Philadelphia.

After authorities secured the scene at the Tree of Life synagogue, Samet gave eye-witness testimony to police. Alexandra Wimley

Despite his losses, Samet approaches each day with faith and joy: swimming, reading, and listening to Torah scholars on podcasts.

President Donald Trump shared the highlights of Samet’s story at his second State of the Union speech in February 2019, prompting both houses of Congress to sing Samet “Happy Birthday” in a rare moment of national unity.

He believes he will live to bear witness, and would like to do so to achieve some measure of justice for the victims of the Tree of Life massacre — and in honor of his late mother.

“My mother was a fighter,” said Samet. “I don’t need encouragement to testify, not even from my mother, but would she support me in that? Absolutely.

“I would like to do it for the sake of justice.”

This entry was written by Heather Robinson and posted on March 29, 2022 at 9:37 pm and filed under Features. permalink. Follow any comments here with the RSS feed for this post. Keywords: . Post a comment or leave a trackback: Trackback URL. */?>